Author: Kirsi Peltonen, Department of Mathematics and Systems Analysis, Aalto University

Fold2 project enabled my research exchange visit to the University of Tokyo 15.10.-15.11.2024 hosted by Tomohiro Tachi, professor of Arts and Sciences. He is a world-leading expert of origami design, 3D and kinematic forms and function through geometry and computation in architecture and engineering. He has developed computational origami tools e.g. ‘Origamizer’, ‘Freeform Origami’, and ‘Rigid Origami Simulator’ all available at https://origami.c.u-tokyo.ac.jp/ for research use. His active and versatile research group at TachiLab curiously scrutinize phenomena and shapes around us as a starting point of investigations to understand and further develop kinematic and functional systems. Basic ideas behind the fluid nature of structural origami, dealing with any interesting structural study related to surface folding, can be found from a survey article [1]. The open and inclusive research environment at TachiLab was highly inspiring and provided vastly new perspectives and ideas for future explorations in Fold project and beyond.

During my visit, I was privileged to stay at the Faculty House (fig 1) of the green Komaba I campus in Meguro City, Tokyo. Through several changes from a hunting preserve for shogun in the 18th century to an agricultural school in the 19th century and the First Higher School of Japan in the 20th century, it became home of College of Arts and Sciences and other programs of the University of Tokyo. The neighbouring Komaba II,III campuses offer notable modern architecture designed by Hiroshi Hara (fig 2) for the Institute of Industrial Science and other research institutes just next to Japan Folk Crafts Museum buildings (fig 3).

Figure 1 Komaba Faculty House. Figure 2 Architecture of Komaba II Campus. Figure 3 Residence of Muneyoshi (Soetsu) Yanagi – 1889-1961 at Japan Folk Craft Museum next to Komaba campus area.

Komaba campus is conveniently located within a walking distance from Shibuya, special ward and major commercial centre of Tokyo. The main gate of Komaba (fig 4), next to Komaba-tōdaimae Station, invites students, faculty, and visitors to join the campus, that is easily reached from any part of Tokyo thanks to an extensive metro network. Lively campus life is supported by active learning environments, lecture halls, severe sports facilities, fluent logistics, amazing trees, attracting alleys, cozy parks, versatile cafeterias, and various multipurpose spaces that promote social interaction between students and faculty members (figs 5).

Figure 4 The main gate of Komaba campus. Figure 5a Architecture at Komaba I campus. Figure 5b Student restaurants and shops at Komaba I.

Figure 5c Ginkgo tree alley at Komaba I. Figure 5d A cherry tree at Komaba I. Figure 5e Compost structure for fallen leaves at Komaba I. Figure 5f A fir next to Komaba Museum.

Green campus naturally provides a lot of inspiration and content to research for TachiLab. The general goal of their work is to try to understand the relationship between spatial forms and function to make them designable. The starting point is to appreciate the shapes around us, then unravel them from the perspective of geometry and computational methods, aiming to realize novel kinematic and functional systems. Two main themes are “origami”, the behaviors accompanying surface folding, and “structural tessellation”, the geometry of modular systems with consistent spatial connections. Potential outputs of structural origami and tessellations include deployable and repeatedly foldable temporary structures, functional and reprogrammable cellular materials, and control devices for light, heat, or sound. The research group is interested in both understanding and creating phenomena. Topics of research include computational origami, self-assembly and self-folding, origami engineering, polyhedral tessellation, cellular material, structural morphology, deployable structures, kinematic design, and computational fabrication. From hands-on crafting with sheets of paper Tachi has developed ways to formulate research questions, develop theories to computationally solve problems and collaborate with experts from various fields to bring these ideas to industrial application. His ‘Universal Initiative’ aiming to unite the principles of folding found in nature and art to create adaptive, multifunctional artifacts. The goal is in adaptive design that addresses diverse needs and occasions. His framework for collaboration is highly inclusive, inviting artists, scientists and students to the same table driving both education and research achievements. Taking a careful look of local nature and plants growing around the campus is a valuable possibility (figs 6). Studying how and why do certain plants grow as they do, to gain a particular shape in space, is an endless source for inspiration and research across disciplines.

Figures 6a-f.

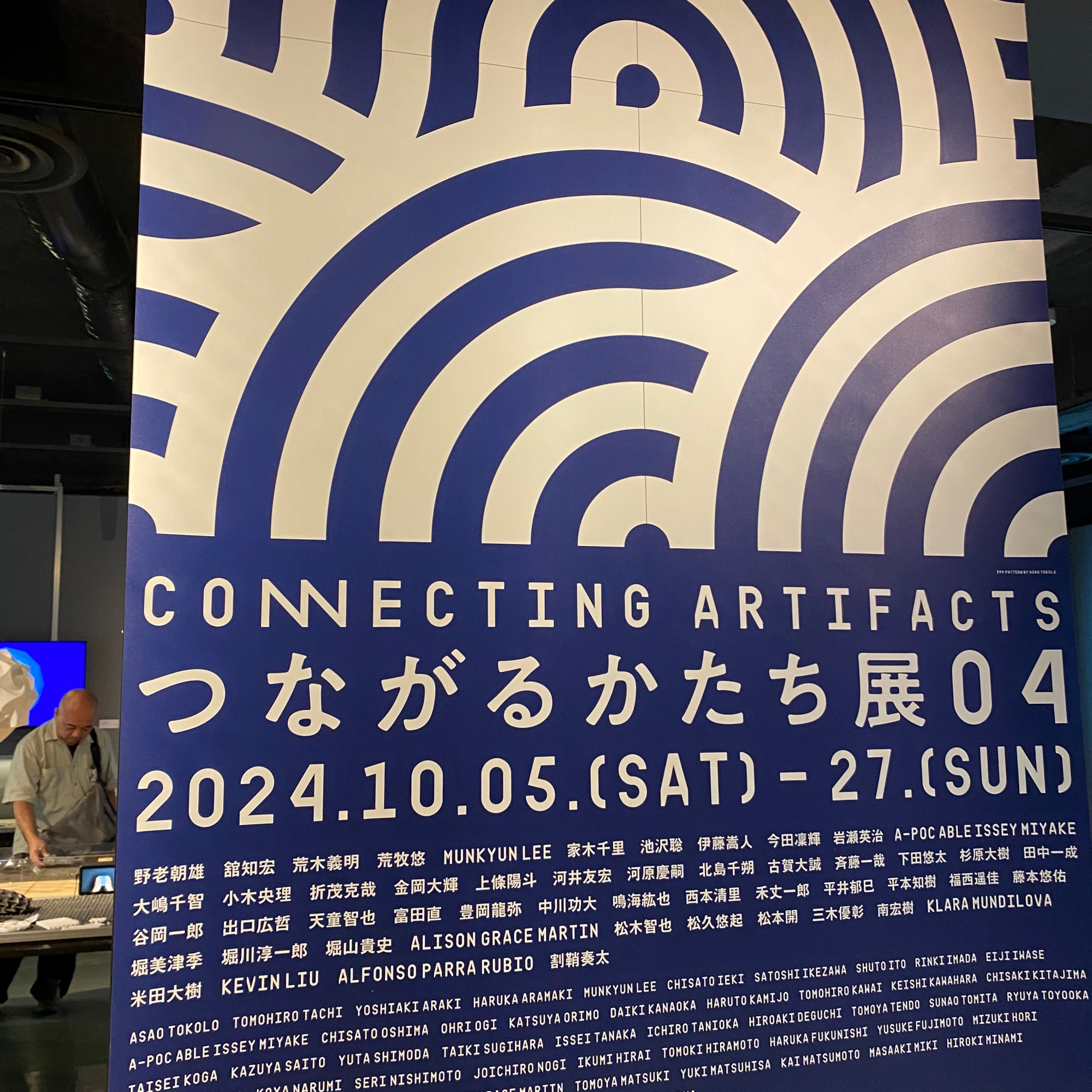

I was fortunate to visit exhibition ‘Connecting Artifacts´ at Science and Technology Museum at the beautiful Kitanomarukoen, Chiyoda City (figs 7).

Figures 7a-d.

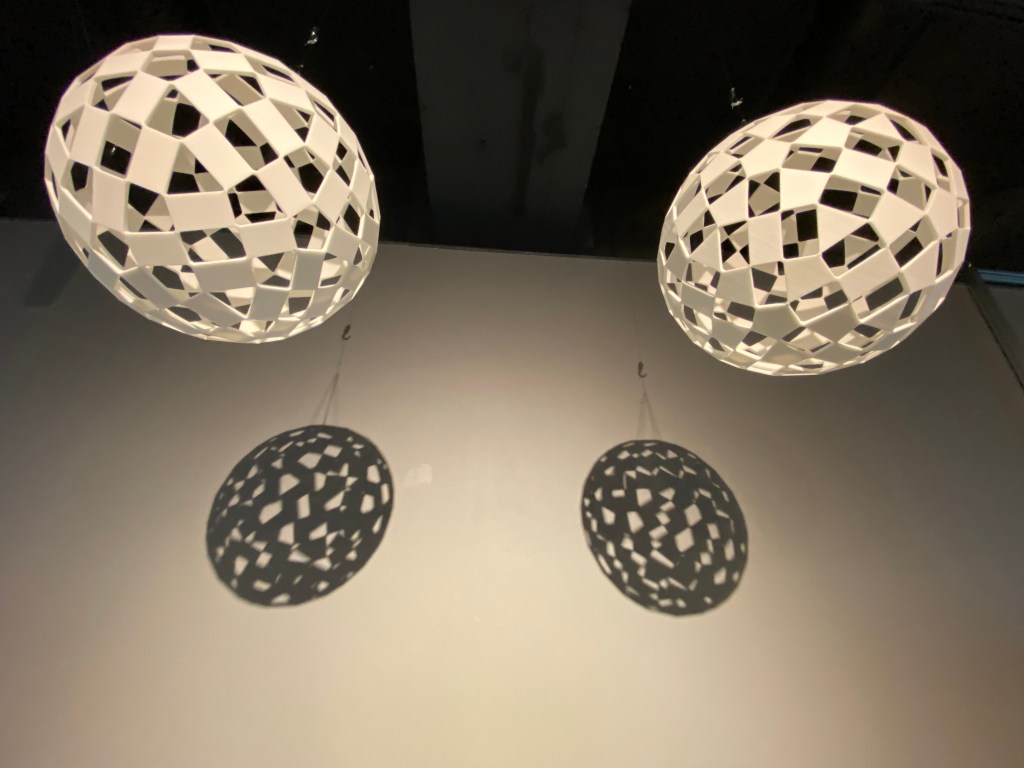

This sequence of exhibitions originated by Tachi and visual artist Asao Tokolo started first in 2021 at the Komaba College Art Museum of the University of Tokyo. Tokolo and his design gained international attention when his graphic artwork ‘Harmonised Chequered Emblem’ was selected to represent the Tokyo 2020 Olympic and Paralympic Games. A related structure, that becomes a one degree of freedom mechanism which can contract the rectangular gaps in the pattern into zero-area slits via kirigami method was showcased at the virtual Bridges conference exhibition 2020 [2]. Inspired by this work on three types of rhombuses and inscribed rectangles (fig 8) Kanata Warisaya, a PhD student in architecture, created families of kinematically compatible auxetic tessellations of different topological types [3].

Figure 8 Tokolo spheres at Connecting Artifacts 04.

The exhibition space for ‘Connecting Artifacts 04’ at the Tokyo Science and Technology Museum was arranged so that in addition to look at fascinating objects, there was a lot of possibilities for hands-on experience of the shapes, building, playing, and studying properties of different structures and mechanisms (fig 9).

Figure 9 Exhibition room for ‘Connecting Artifacts 04’.

Samples of an Inkjet 4D printing proposal was introduced in the exhibition (fig 10). This is a self-folding fabrication method of 3D origami tessellations by printing 2D patterns on both sides of a heat-shrinkable base sheet and using a commercialized inkjet ultraviolet (UV) printer. Compared to the earlier folding-based 4D printing approaches using fused deposition modeling 3D printers, this method has merits in more than 1200 times higher resolution in terms of the number of self-foldable facets, 2.8 times faster printing speed, and optional full color decoration [4].

Figure 10 A selection of self-folded inkjet bracelets.

An interesting proposal for a design method of membrane tensegrity structures was exemplified in the exhibition (fig 11). This method is based on solving the inverse problem using freeform origami tessellations by generalizing Ron Resch’s patterns from the 60’s and 70’s [5]. Generating an origami tessellation and replacing the mountain creases of the tessellation with struts and the other parts with a membrane under initial tension, the tessellation can be formed as a tensegrity structure. Inspired by this phenomenon, fourth year undergraduate student Joichiro Nogi from the Department of Interdisciplinary Sciences has started to develop more detailed analysis methods of the skin and spine structure of burrfish (fig 12). This type of fish has short spines that overlap without obstructing each other under expansion of the skin.

Figure 11 3D printed PLA on mountain folds of a planar tessellation on stretchable nylon fabric. Figure 12 Burrfish.

Rinki Imada, a PhD student at TachiLab, has studied so called non-uniform origami tessellations, whose crease pattern is based on alternating unit cells. Non-uniform folding allows nonlinear phenomena that are impossible through uniform folding, where the crease pattern consists of identical cells only. There is no universal model for non-uniform folding, and the underlying mathematics for some observed phenomena remains unclear. Wavy folded states that can be achieved through non-uniform folding of the tubular origami tessellation called waterbomb tube, are an example (fig 13). In [6], the kinematic coupled motion of unit cells within waterbomb tube is formulated as a discrete dynamical system and identified a correspondence between its quasiperiodic solutions and wavy folded states. In [7], it is shown that the wavy folded state is a universal phenomenon that can occur in a family of rotationally symmetric tubular origami tessellations. The result demonstrates the potential of the dynamical system model as a universal model for nonuniform-folding or a tool for designing metamaterials.

Figure 13 The wavy folded state of an origami tube.

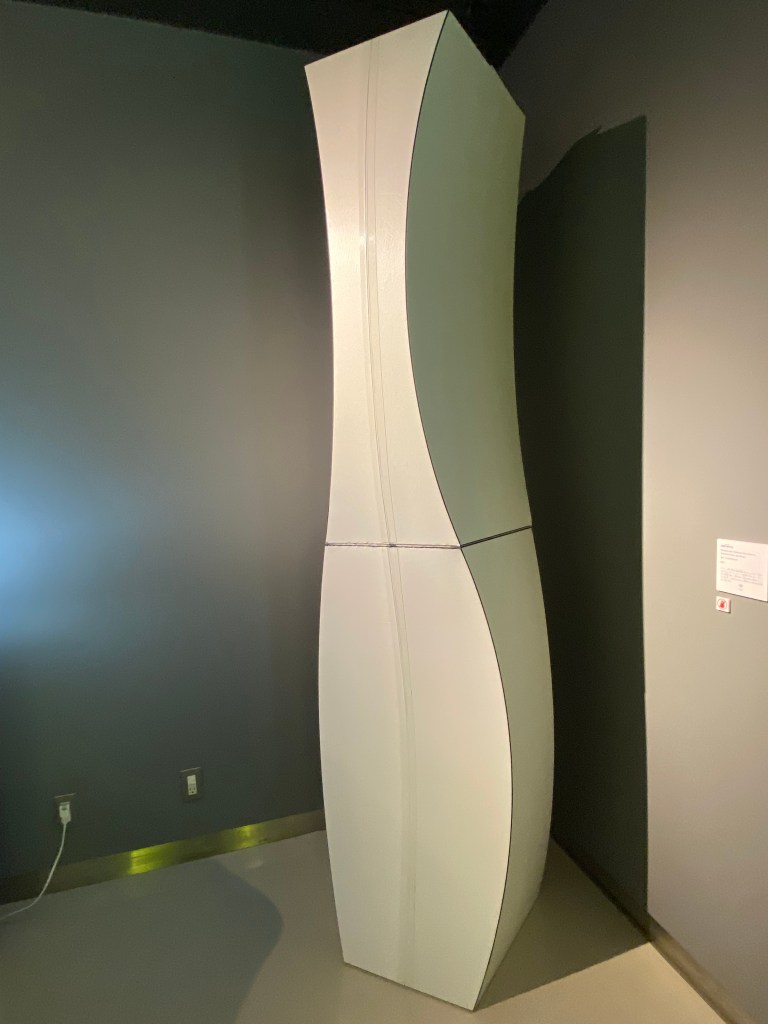

Article [8] proposes a novel modular building system using curved-crease origami columns. A building-scale cardboard model was showcased in the exhibition (fig 14). The column is designed with a non-rotationally symmetric trapezoidal cross-section profile and an elastica curvature surface profile. The selected profile and surface curvature allow for flexible tessellation and interlocking of adjacent columns, forming intricate, quasi-continuous wall surfaces using a single repeating component.

Figure 14 A curved-crease origami block.

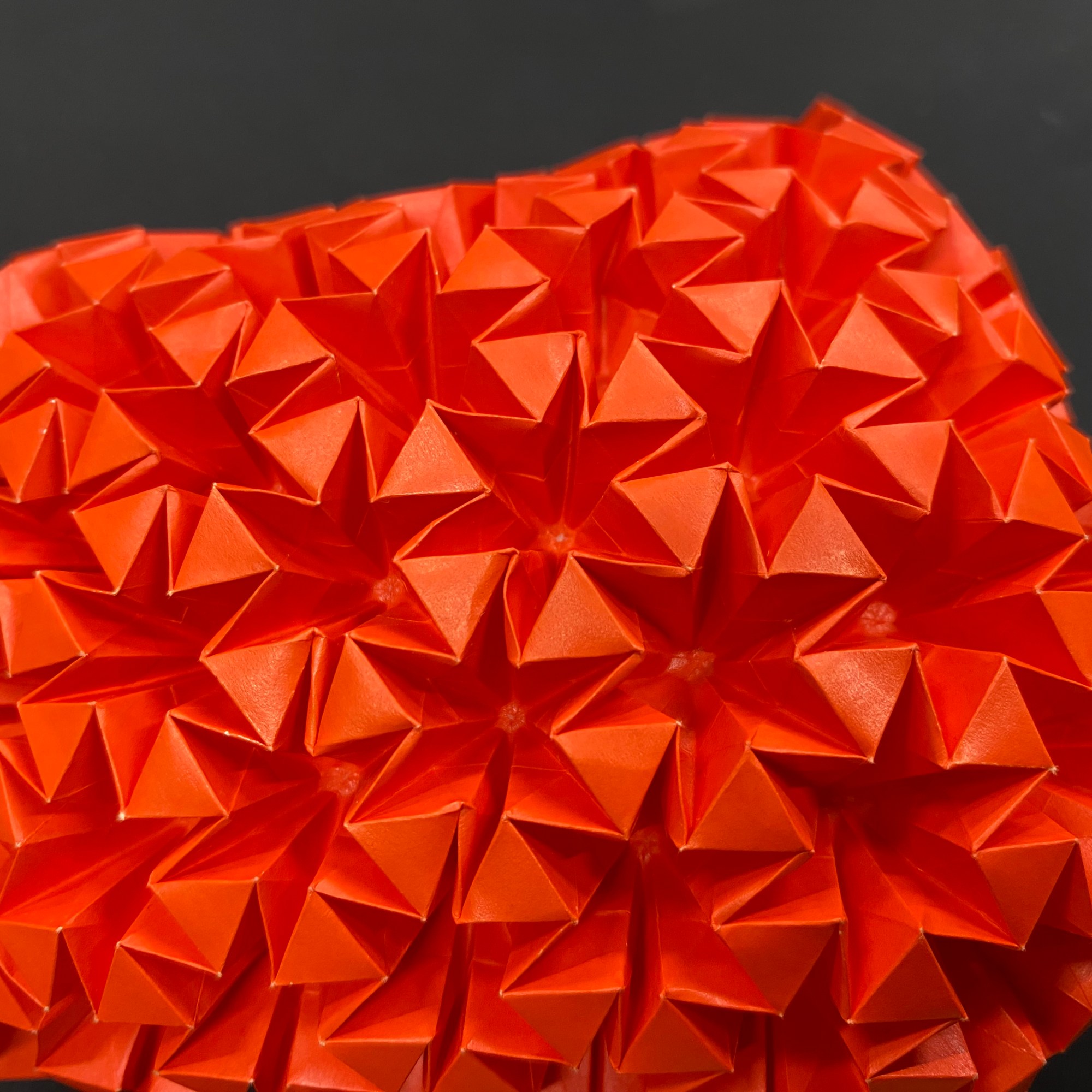

Tachi’s Bunny (fig 15) is a model example of his developments [9] to produce families of origami tessellations from given polyhedral surfaces. The resulting tessellated surfaces generalize the patterns proposed by Ron Resch and allow the construction of an origami tessellation that approximates a given surface. These patterns are achieved by first constructing an initial configuration of the tessellated surfaces by separating each facets, and inserting folded parts between them based on the local configuration. The initial configuration is then modified by solving the vertex coordinates to satisfy geometric constraints of developability, folding angle limitation, and local non-intersection.

Figure 15 Tachi’s Bunny.

Science museum planetarium provided a wonderful platform to experience exhibition pieces and other origami and kirigami structures from inside (fig 16). This special event, including talks by Tokolo and Tachi, was arranged in the context of the exhibition.

Figure 16 Inside connecting artifacts.

Students at TachiLab share multipurpose premises full of inspiring models and prototypes at Komaba 1 campus (fig 17). Tightly packed and well-organized storage boxes containing material of former and current students, faculty, and visitors provide endless insight and motivation for further studies and research. Students were also actively sharing their work with me and Lucia Stein-Montalvo, Assistant Professor of Civil and Environmental Engineering at Northwestern University, whose visit partly overlapped with my visit at Tokyo. A special session was arranged, where all students presented us their most recent work (fig 18). This was a very fruitful starting point for further discussions.

Figure 17 Students at TachiLab. Figure 18 TachiLab students presenting their work.

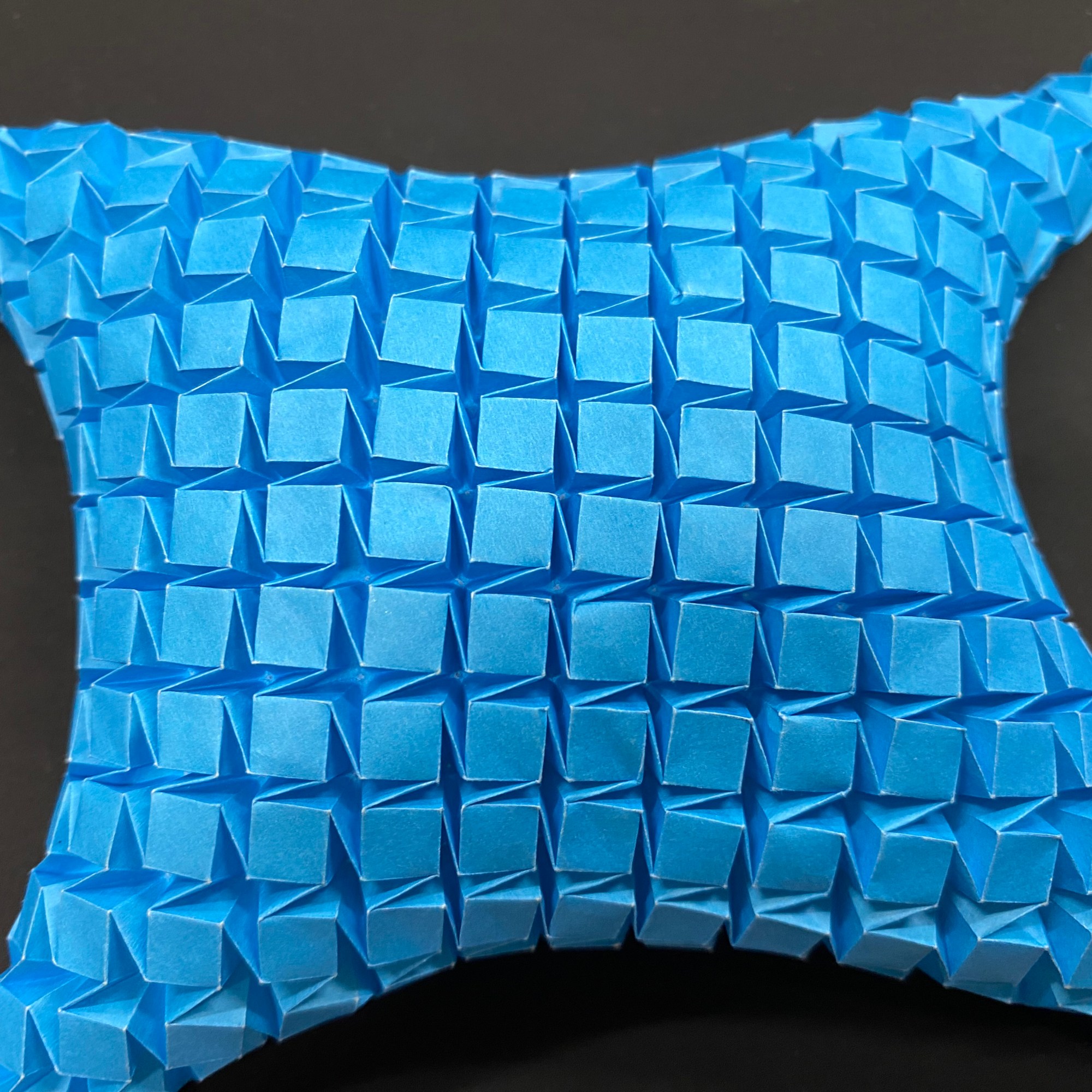

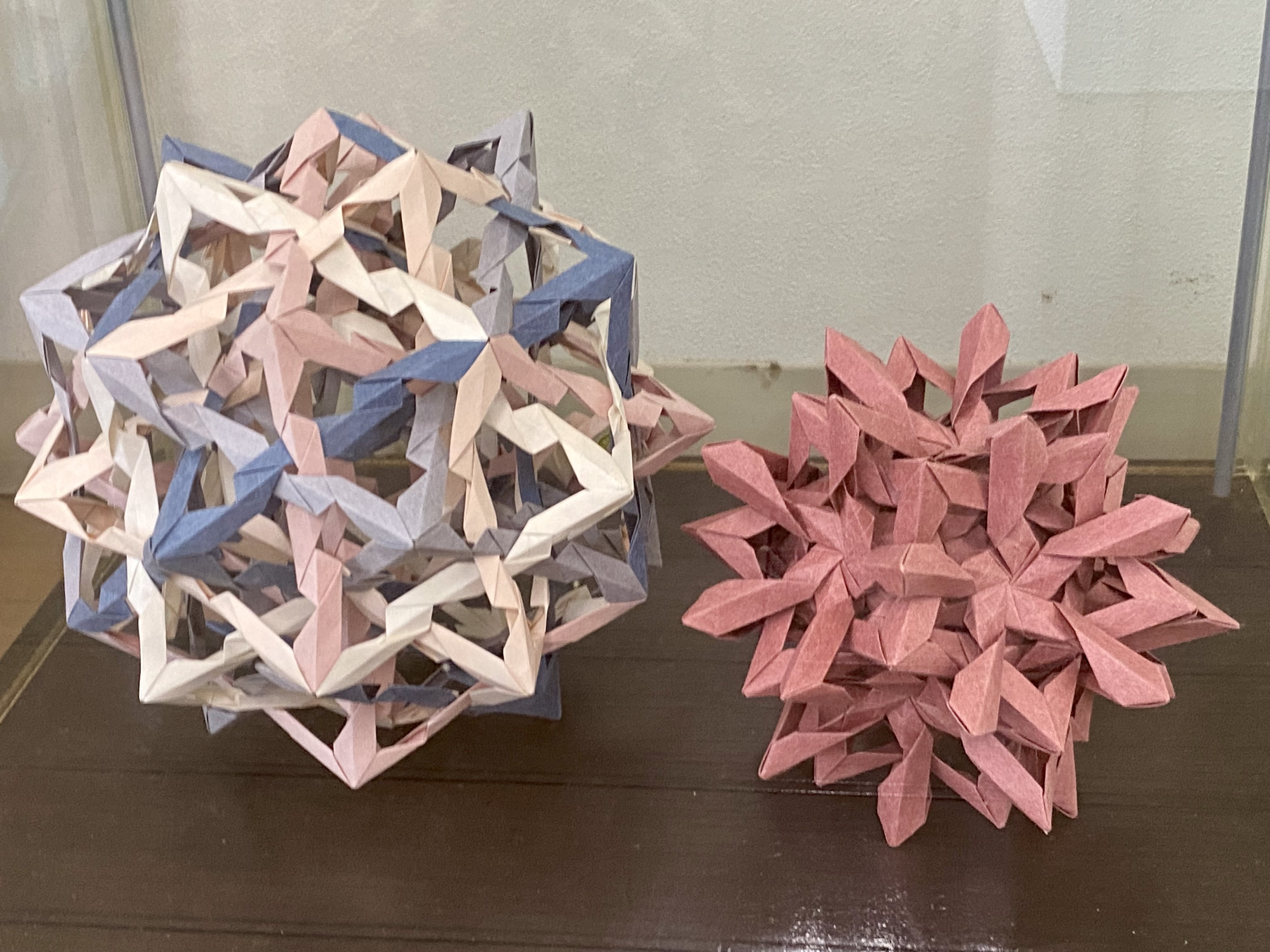

Student Akito Adachi presented his work that included several beautiful generalizations of well-known Ron Resch patterns (figs 19) with congruent waterbomb patterns at each vertex of a tessellation (figs 20).

Figure 19a Ron Resch triangle base pattern. Figure 19b Ron Resch square base pattern. Figure 20a Combination of parallelograms and triangles by Adachi. Figure 20b Combination of hexagons, parallelograms and triangles by Adachi.

Student Seri Nishimoto has studied various transformable surface mechanisms via geodesic scissor systems. The scissors-like grid shells composed of members bent in the out-of-plane direction have structural advantages: the ease of deployment as a one-degree-of-freedom system and the stability as it is modeled as a shell once the scissors’ transformation is fixed. However, it is impossible to generate a freeform doubly curved surface from a single grid while maintaining the geodesics. In article [10], an approach based on assembling multiple units of grid systems to obtain a variety of transformable surfaces is proposed. In figure 21, a scissor mechanism opening from a straight flat cylinder to a constant negative curvature pseudosphere is shown [11]. In [12], geometric properties of a family of polyhedra obtained by folding a regular tetrahedron along triangular grids is shown. Each polyhedron is identified by a pair of nonnegative integers. The polyhedron can be cut along a geodesic strip of triangles to be decomposed and unfolded into one or multiple bands. By a proper choice of pairs of numbers, a common triangular band that folds into different polyhedra, can be created. Tetrahedron case is demonstrated in figure 22.

Figure 21 Pseudosphere scissor mechanism. Figure 22 Zipper constructions of a tetrahedron.

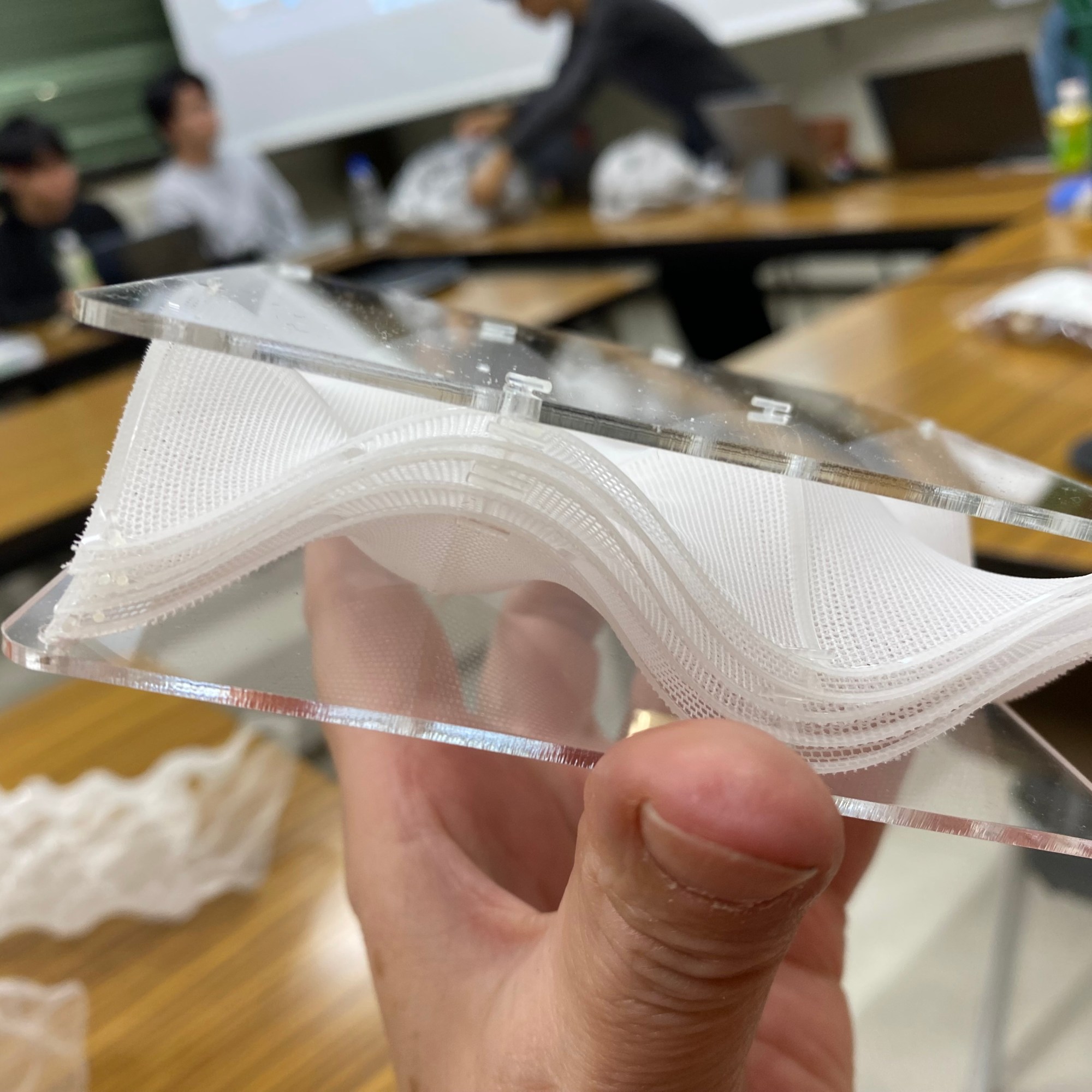

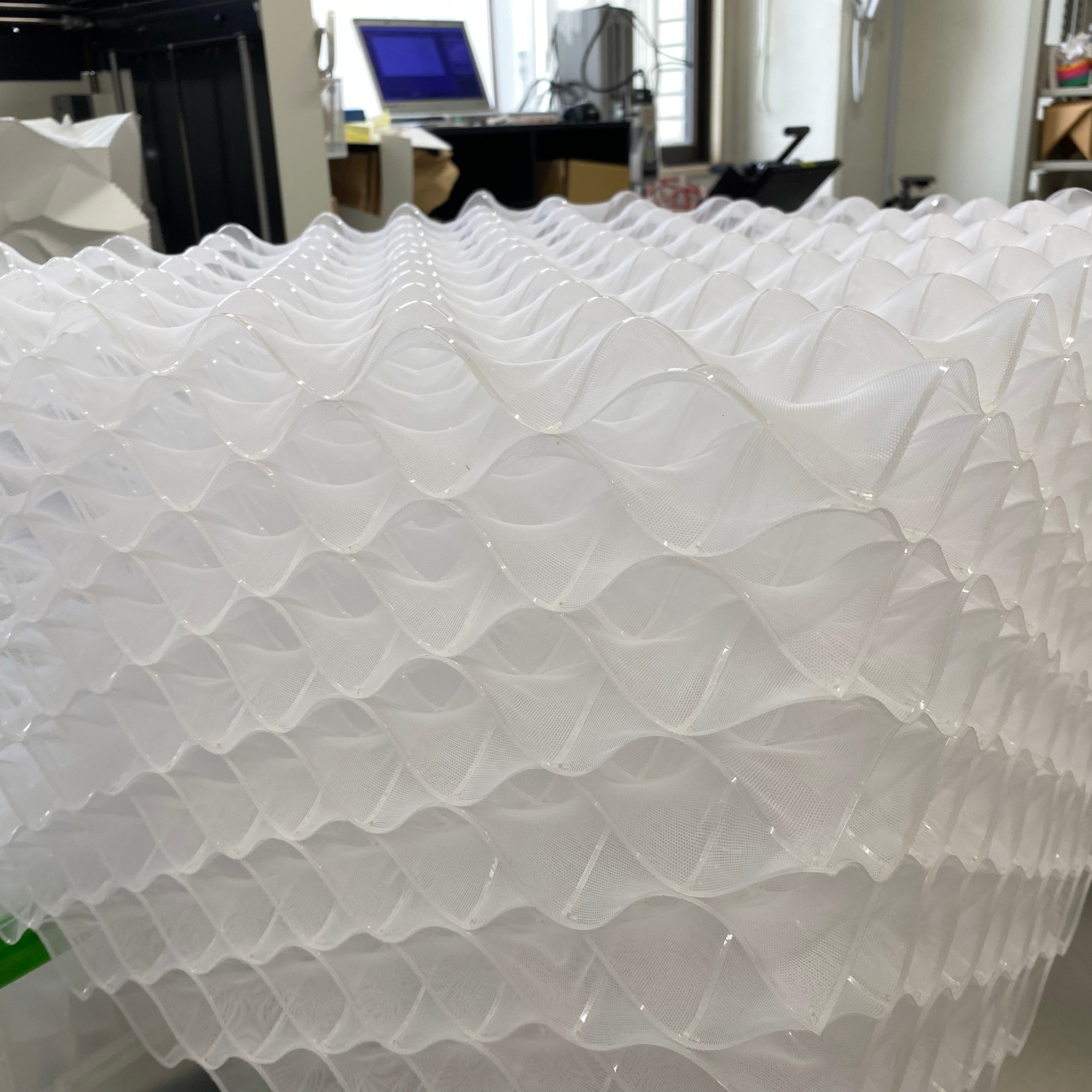

Connections to textile and fashion industry is developed in several works of TachiLab students. In figures 23 layered textiles with periodic curved surfaces are shown. They are obtained through 4D fabrication technology. Each layer has bi-stability and can be flipped, allowing the whole piece to unfold as a multi-stable structure. It continues to bounce around, thanks to a primitive expansion and contraction mechanism using a single piece of fishing line and a sheet of acrylic. Programmable active textiles are discussed in article [13]. In figure 24, some ongoing collaboration with TachiLab and Mount Fuji Textile Ltd is shown. Weaving the origami pattern directly to the fabric is based on Jacquard technique, that employs a punched card system to control individual warp threads, enabling the creation of intricate designs with remarkable precision. One of the notable advantages of Jacquard weaving is its efficiency in mass production. Unlike traditional weaving, where each piece may vary slightly due to the weaver’s skill and memory, Jacquard looms can reproduce the same design consistently and at a rapid pace. This consistency is highly valuable in industries where large quantities of fabric are required, such as in the production of upholstery for furniture or high-end fashion.

Figure 23a A layered textile structure in the unfolded form. Figure 23b A layered textile structure in the folded form. Figure 23c A layered textile cube in the unfolded state. Figure 24 Jacquard weaved textile samples at TachiLab.

A novel family of structures, that can be inflated from a plane to form a three-dimensional surface using articulated straight pouches with inextensible membranes is introduced in [14]. Specifically, a modular design using a quadrangle surrounded by four slender pouches, whose inflation causes the surface to form a saddle shape is proposed. In addition, a fabrication method using heated nylon films with heat adhesives separated by paper mask patterns inside is developed. Finally, a geometric model to explain and predict the out-of-plane deformation and the bi-stability effect inherited in this structure is presented. A curved fold produced via this method is shown in figure 25. I was inspired by the possibility to produce tessellations via this method. With Yiwei Zhang and Tachi, we started to ideate crease patterns suitable for this method (fig 26). Parallel to this work we started, jointly with Stein-Montavalo, to look at bi-stability issues related to curved folding that she has studied earlier [15]. Inspired by the works of Ekaterina Lukasheva [16] and Klara Mundilova [17] we hope to find new approaches to understand these structures better. Zhang produced a bunch of efficient molds (fig 27) to design crease patterns according to instructions in [16].

Figure 25 An air pouch curved crease. Figure 26 An air pouch tessellation. Figure 27 Molds for curved crease patterns.

During my visit in Tokyo, I had a possibility to tour some of the local origami centres.

Gallery Origami House at Hakusan, Bunkyo-ku, is a permanent exhibition space for origami. This small gallery full of amazing origami pieces (figs 28), publications of The Japan Origami Academic Society (JOAS) and related material, was opened in April 1989 with the aim of spreading the word about origami. JOAS has a central role in promoting the dissemination and specialized study of origami in all its cultural and academic aspects. In addition, it has the broader purpose of organizing a variety of activities in order to facilitate the personal interaction of folders internationally. In 1989, four young origami artists came together to hold a joint exhibition of their collective origami works. Formed from this collaboration was the first predecessor to “Origami Tanteidan”. From there, the group steadily increases, exhibiting models with the support of many origami enthusiasts. By the year 2000 it has led to a wide range of activities for the current organization. JOAS promotes the dissemination of origami and origami related research, in addition to encourage the interaction between origami enthusiasts from all around the world. JOAS engages in the professional study of origami creation, criticism, and critical analysis; origami research in technology, mathematics, education, history, reference, and copyright; and the engineering, design, and commercial applications of origami. JOAS spreads the word of origami by improving the social awareness of the world of origami, expanding the activities available to origami enthusiasts, and assisting in the development of talented folders.

Figures 28a-c.

I am grateful to Tomohiro Tachi for his hospitality, time, and fruitful discussions with his team during my stay at the University of Tokyo. This research exchange visit was funded by Business Finland Fold2 project. The visit greatly enhanced my understanding about the current state of origami research although it was possible to present only a small portion of the ongoing research at TachiLab in this short text. Tomohiro Tachi will be the keynote speaker of the webinar to be arranged in 19th March in the context of Fold2 project.

References:

[1] Tomohiro Tachi: Introduction to Structural Origami, Journal of the International Association for Shell and Spatial Structures, Vol. 60 No. 1 March n. 199, pp. 7-18(12) 2019.

[2] Kanata Warisaya, Asao Tokolo, Tomohiro Tachi: Harmonized Chequered Mechanism, Bridges Conference Exhibition 2020.

[3] Kanata Warisaya, Jun Sato, Tomohiro Tachi: Freeform auxetic mechanisms based on corner-connected tiles, Journal of the International Association for Shell and Spatial Structures, Vol. 63 (2022) No. 4 December n. 214, pp. 263-271(9), 2022.

[4] Koya Narumi, Kazuki Koyama, Kai Suto, Yuta Noma, Hiroki Sato, Tomohiro Tachi, Masaaki Sugimoto, Takeo Igarashi, Yoshihiro Kawahara: Inkjet 4D Print: Self-folding Tessellated Origami Objects by Inkjet UV Printing, ACM Transactions on Graphics 42(4) 13 pages, 2023.

[5] Y. Shimoda, K. Suto, S. Hayashi, T. Gondo, T. Tachi: Developable Membrane Tensegrity Structures Based on Origami Tessellations, Advances in Architectural Geometry 2023, pp.303-312, 2023.

[6] Rinki Imada, Tomohiro Tachi: Conservative Dynamical Systems in Oscillating Origami Tessellations, Lecture Notes on Data Engineering and Communications Technologies, 146, 308-321, 2023.

[7] Rinki Imada, Tomohiro Tachi: Undulations in tubular origami tessellations: A connection to area-preserving maps, Chaos 33, 2023.

[8] Munkyun Lee, Mahmoud Abu-Saleem, Tomohiro Tachi, Joe Gattas: A lightweight building construction system using curved-crease origami blocks, To appear in 8OSME.

[9] Tomohiro Tachi: Freeform Origami Tessellations by Generalizing Resch’s Patterns, Proceedings of the ASME 2013 International Design Engineering Technical Conferences and Computers and Information in Engineering Conference, August 4-7, 2013, Portland, Oregon, USA.

[10] Seri Nishimoto, Tomohiro Tachi: Transformable Surface Mechanisms by Assembly of Geodesic Grid Mechanisms, Advances in Architectural Geometry 2023.

[11] Fuki Ono, Haruto Kamijo, Miwako Kase, Seri Nishimoto, Kotaro Sempuku, Mizuki Shigematsu, Tomohiro Tachi: Growth-induced transformable surfaces realized by bending-active scissors grid, Architectural Intelligence 3(1):1-18, 2024.

[12] Seri Nishimoto, Takashi Horiyama, Tomohiro Tachi: Geodesic Folding of Regular Tetrahedron, Journal for Geometry and Graphics, Volume 26, No. 1, 81–100, 2022.

[13] Haruto Kamijo, Tomohiro Tachi: Curvature Design of Programmable Textile,

[14] Yiwei Zhang, Tomoya Tendo, Tomohiro Tachi: Modular design of multistable pneumatic structures from a flat pattern of air pouches. Journal of the International Association for Shell and Spatial Structures, 64(4), 298-305.

[15] Jessica Flores, Lucia Stein-Montalvo, Sigrid Adriaenssens: Effect of crease curvature on the bistability of the origami waterbomb base, Extreme Mechanics Letters, Vol 57, 2022.

[16] Ekaterina Lukasheva: Curved Origami, 2021.

[17] Klara Mundilova: Gluing and Creasing Paper along Curves: Computational Methods for Analysis and Design, PhD Thesis MIT, 2024.

Senior University Lecturer Kirsi Peltonen at the Yayoi Kusama Museum in Tokyo, November 2024.